La storia postale cinese

La complicata storia postale cinese è strettamente legata ai vari avvenimenti storici che hanno visto il graduale declino della Cina imperiale, gli anni della guerra civile e il periodo dell’occupazione giapponese tra gli anni trenta e gli anni quaranta. Già nel I millennio a.C. in Cina esisteva un servizio postale regolare controllato dal governo della dinastia Zhou. Nel XII secolo, durante la dinastia Yuan, sotto il regno di Kublai Khan, la Cina fu inserita nel sistema Örtöö mongolo. Marco Polo riferì che c’erano 10.000 stazioni postali all’epoca. Inoltre, sempre in quel periodo esisteva un sistema di corrieri privati. Più tardi, nel 1727, grazie al trattato di Kjachta con la Russia, ebbe inizio il primo scambio regolare di posta.

Dinastia Qing

La prima guerra dell’oppio segnò il termine della politica di isolazionismo cinese e portò alla conseguente apertura dei cosiddetti treaty ports, città portuali nelle quali, a partire dal 1844, le diverse nazioni europee aprirono i loro uffici postali. Il sistema postale occidentale iniziò ad espandersi, occupando decine di città sulla costa, sulle rive del Fiume Azzurro e nel sud del paese. Nel 1865 Shanghai organizzò il proprio sistema postale. Nello stesso anno l’inglese Robert Hart tentò di collegare i diversi treaty pots, portando così all’emissione dei primi francobolli cinesi nel 1 maggio 1878, denominati “grandi draghi” (in cinese: 大龍郵票T, dàlóng yóupiào). Su questi francobolli la parola “Cina” era scritta sia in inglese (“China”), che in cinese (中國T, zhōngguó). Inizialmente la posta internazionale veniva smistata solamente a Shanghai. Dopodiché vennero aperti altri uffici postali simili: nel 1882 ce n’erano dodici in tutto. Dal 1 gennaio 1897, il servizi doganali introdotti da Robert Hart divennero ufficialmente il Sistema Postale Imperiale. Tale evento segnò la fine del sistema postale locale a Shanghai e dei corrieri privati introdotti secoli prima. Il nuovo sistema postale scelse di utilizzare i centesimi ed i dollari come unità di valuta. I primi francobolli commemorativi vennero introdotti nell’impero cinese nel 1909, in occasione del primo anniversario del regno dell’imperatore Xuantong. Questa serie di tre francobolli da 2, 3 e 7 centesimi raffigurava il Tempio del Cielo a Pechino.

Governo Beiyang

Con la rivoluzione del 1911 molti francobolli imperiali vennero soprastampati con la dicitura “Repubblica di Cina” (dall’alto verso il basso: 中華民國T, zhōnghuámínguó). Tale operazione veniva eseguita dalla Waterlow & Sons a Londra, negli uffici postali di Shanghai, Fuzhou e Nanchino e in quelli delle città minori, dove venivano utilizzati timbri non ufficiali con gli stessi caratteri. I primi francobolli del nuovo governo vennero emessi il 14 dicembre 1912: le due serie con dodici tagli ciascuna raffiguravano i volti di Sun Yat-sen e Yuan Shikai.

Governo nazionalista

Il 18 aprile 1929 fa la sua prima comparsa Chiang Kai-shek, in un francobollo atto a celebrare l’unificazione della Cina. Il 30 maggio 1929, due giorni prima dell’evento, vennero emessi quattro francobolli con l’immagine del mausoleo di Sun Yat-sen per commemorare i suoi funerali di Stato. La fine del secondo conflitto cino-giapponese fu un periodo di tregua per il governo nazionalista che, tuttavia, dovette far fronte alle forze comuniste. Anche in questo periodo vennero emessi francobolli commemorativi per ricordare il presidente Lin Sen, morto nel 1943, e per celebrare la figura di Chiang e la vittoria degli alleati. Il bisogno di francobolli dal valore più alto, causato dall’inflazione, degenerò nel 1946: i valori di una grande quantità di francobolli, alcuni persino del 1931, vennero cambiati, raggiungendo talvolta un sovrapprezzo di 2.000 $. Fu introdotto un nuovo design, con il volto di Sun Yat-sen, di ben 5.000 $. L’inflazione persistette nell’anno successivo, nel quale venne emesso un taglio da 50.000 $, sempre con Sun Yat-sen, questa volta con un fiore di pruno. Nel 1948 venne raggiunto il valore massimo con una ristampa da 5.000.000 $. Il 1 maggio 1949 il governo cercò di rimediare al problema dell’inflazione introducendo un taglio che non recava appresso alcun prezzo, affinché si potesse sempre adattare all’instabile valore dello yuan. La situazione politica sempre più instabile segnò la fine dell’emissione dei francobolli da parte del governo nazionalista sul territorio della Cina continentale.

Nel 1932 il Giappone creò uno stato fantoccio nella parte nord-orientale della Cina: il Manciukuò. Durante la breve esistenza di questo Paese ci furono delle vere e proprie chimere culturali, anche nell’ambito dei francobolli che, pur essendo influenzati dalla cultura giapponese, conservano le loro caratteristiche cinesi. Nel 1944 venne stampata una serie di francobolli dedicati all’amicizia tra il Manciukuò e il Giappone scritta sia in giapponese che in cinese.

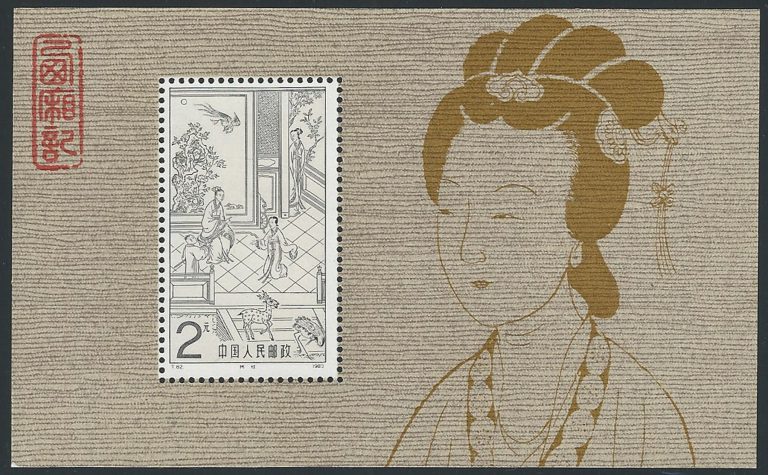

Repubblica Popolare Cinese

Nel 1949 il sistema postale di Pechino venne esteso a tutta la Cina e sostituì i servizi postali che operavano già da anni nei territori sotto il dominio delle autorità comuniste. Molte zone utilizzavano ancora i propri francobolli, finché il 30 giugno 1950 non venne imposto loro il divieto di stampare e vendere tagli regionali. I primi bolli della Repubblica Popolare Cinese vennero emessi l’8 ottobre 1949. Essi consistevano in una serie i quattro francobolli raffiguranti la Porta della pace celeste di Pechino atti a celebrare la prima seduta della conferenza politica consultiva del popolo cinese.

Grande rivoluzione culturale

“La grande vittoria della rivoluzione culturale”: francobollo mai emesso che mostra Mao Zedong e Lin Biao acclamati da una grande folla.

Durante la rivoluzione culturale, per motivi politici, vennero ritirati molti francobolli. Diverse serie non furono mai messe sul mercato; tuttavia, degli uffici postali locali riuscirono a venderne alcune in maniera non ufficiale prima della data della loro emissione. Tali serie sono particolarmente rinomate per la loro rarità: per esempio, un francobollo mai emesso atto a celebrare il quarantesimo anniversario dello stabilimento della base rivoluzionaria di Jinggangshan, conosciuto come “Grande cielo blu” (大蓝天S, dàlántiān), mostrava le figure di Mao Zedong e di Lin Biao che guardavano la piazza Tian’anmen dall’alto. Dopo il tradimento di quest’ultimo tutte le copie del francobollo vennero eliminate. I pochi tagli sopravvissuti a tale processo di distruzione sono pezzi estremamente rari e ambiti dalla comunità filatelica.

Nel 1984 in Cina vi erano 53.000 uffici delle poste e telecomunicazioni e 5.000.000 km di tratte postali, tra cui 240.000 km di rotte ferroviarie, 624.000 km di autostrada e 230.000 km di posta aerea. Iniziarono ad essere spediti grandi quantitativi di lettere, giornali e riviste.

La Cina rimase esclusa per molti anni dall’Unione postale universale. Pur riportando il valore dei francobolli in numeri arabi, non sentì il bisogno di aggiungere il nome del paese in caratteri latini come richiesto dalle regole dell’UPU. La dicitura “China” iniziò ad essere integrata sulle affrancature a partire dal 1992. I francobolli cinesi si distinguono da quelli di qualsiasi altro paese per via del numero seriale presente nell’angolo in basso a sinistra. (Per esempio, l’emissione della colomba della pace, di cui abbiamo parlato supra, è contrassegnata dalla sigla “5.3-2”, che indica che il francobollo in questione è il secondo di una serie di tre, e che la serie è la quinta emissione in totale. Tale sistema di numerazione venne seguito solamente per i francobolli speciali e per quelli commemorativi;)

Per la trascrizione in alfabeto latino della pronuncia delle parole in cinese si è fatto riferimento al sistema Hànyǔ Pīnyīn.

C.M.

China’s complicated postal history is closely linked to the various historical events that saw the gradual decline of Imperial China, the years of civil war and the period of Japanese occupation between the 1930s and 1940s. As early as the 1st millennium BC, China had a regular postal service controlled by the government of the Zhou dynasty. In the 12th century, during the Yuan dynasty, under the reign of Kublai Khan, China was included in the Mongol Örtöö system. Marco Polo reported that there were 10,000 postal stations at that time. In addition, a private courier system existed at that time. Later, in 1727, thanks to the Treaty of Kjachta with Russia, the first regular exchange of mail began.

Qing Dynasty

The First Opium War marked the end of the Chinese policy of isolationism and led to the consequent opening of the so-called treaty ports, port cities in which the various European nations opened their post offices from 1844 onwards. The western postal system began to expand, occupying dozens of cities on the coast, on the banks of the Yangtze River and in the south of the country. In 1865 Shanghai organised its own postal system. In the same year, the Englishman Robert Hart attempted to connect the different treaty pots, leading to the issuance of the first Chinese postage stamps on 1 May 1878, called ‘great dragons’ (Chinese: 大龍郵票T, dàlóng yóupiào). On these stamps, the word ‘China’ was written in both English (‘China’) and Chinese (中國T, zhōngguó). Initially, international mail was only sorted in Shanghai. After that, other similar post offices were opened: by 1882 there were twelve in total. From 1 January 1897, the customs services introduced by Robert Hart officially became the Imperial Postal System. This event marked the end of the local postal system in Shanghai and the private couriers introduced centuries earlier. The new postal system chose to use cents and dollars as currency units. The first commemorative stamps were introduced in the Chinese Empire in 1909 to mark the first anniversary of the reign of Emperor Xuantong. This set of three stamps of 2, 3 and 7 cents depicted the Temple of Heaven in Peking.

Beiyang Government

With the revolution of 1911, many imperial stamps were overprinted with the words “Republic of China” (from top to bottom: 中華民國T, zhōnghuámínguó). This was done by Waterlow & Sons in London, at post offices in Shanghai, Fuzhou and Nanjing and in smaller cities, where unofficial stamps with the same characters were used. The first stamps of the new government were issued on 14 December 1912: the two sets with twelve denominations each depicted the faces of Sun Yat-sen and Yuan Shikai.

Nationalist government

On 18 April 1929 Chiang Kai-shek made his first appearance on a postage stamp celebrating the unification of China. On 30 May 1929, two days before the event, four stamps were issued with the image of Sun Yat-sen’s mausoleum to commemorate his state funeral. The end of the Second Sino-Japanese Conflict was a period of respite for the Nationalist government, which, however, had to cope with Communist forces. Also during this period, commemorative stamps were issued to remember President Lin Sen, who died in 1943, and to celebrate Chiang and the Allied victory. The need for higher-value stamps, caused by inflation, escalated in 1946: the values of a large number of stamps, some even dating back to 1931, were changed, sometimes reaching a premium of $2,000. A new design, with the face of Sun Yat-sen, was introduced, costing as much as $5,000. Inflation persisted in the following year, when a $50,000 denomination was issued, again with Sun Yat-sen, this time with a plum blossom. In 1948 the maximum value was reached with a $5,000,000 reprint. On 1 May 1949, the government tried to remedy the inflation problem by introducing a denomination that carried no price, so that it could always be adjusted to the unstable value of the yuan. The increasingly unstable political situation marked the end of the Nationalist government’s issuance of postage stamps in mainland China.

In 1932 Japan created a puppet state in the north-eastern part of China: Manchukuò. During the short existence of this country, there were cultural chimeras, even in the area of postage stamps, which, although influenced by Japanese culture, retained their Chinese characteristics. In 1944, a series of stamps was printed dedicated to the friendship between Manchukuò and Japan written in both Japanese and Chinese.

People’s Republic of China

In 1949, the Beijing postal system was extended to the whole of China and replaced the postal services that had already been operating for years in the territories under communist rule. Many areas still used their own postage stamps, until the ban on printing and selling regional denominations was imposed on 30 June 1950. The first stamps of the People’s Republic of China were issued on 8 October 1949. They consisted of a set of four stamps depicting the Heavenly Peace Gate in Peking to celebrate the first session of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

Great Cultural Revolution

“The Great Victory of the Cultural Revolution”: a stamp never issued showing Mao Zedong and Lin Biao being cheered by a large crowd.

During the Cultural Revolution, many stamps were withdrawn for political reasons. Several series were never put on the market; however, local post offices managed to sell some unofficially before their issue date. Such series are particularly renowned for their rarity: for instance, a never-issued stamp celebrating the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Jinggangshan revolutionary base, known as the ‘Big Blue Sky’ (大蓝天S, dàlántiān), showed the figures of Mao Zedong and Lin Biao looking down on Tian’anmen Square from above. After the latter’s betrayal, all copies of the stamp were scrapped. The few denominations that survived this destruction process are extremely rare and coveted pieces by the philatelic community.

In 1984 there were 53,000 post and telecommunication offices and 5,000,000 km of postal routes in China, including 240,000 km of railway routes, 624,000 km of highway and 230,000 km of air mail. Large quantities of letters, newspapers and magazines began to be sent.

China was excluded from the Universal Postal Union for many years. Although it marked its stamps in Arabic numerals, it did not feel the need to add the country’s name in Latin characters as required by UPU rules. The wording ‘China’ began to be integrated on postage stamps from 1992. Chinese stamps can be distinguished from those of any other country by the serial number in the bottom left corner. (For example, the Peace Dove issue mentioned above is marked “5.3-2”, indicating that the stamp in question is the second in a series of three, and that the series is the fifth issue in total. This numbering system was only followed for special and commemorative stamps;)

For the transcription into the Latin alphabet of the pronunciation of words in Chinese, reference was made to the Hànyǔ Pīnyīn system.

C.M.